You can click on each title below to go straight to the blog you're looking for, or choose the relevant date from the Archives on the right.

April 2012

Images from the Silk Road – Rainbow Silk

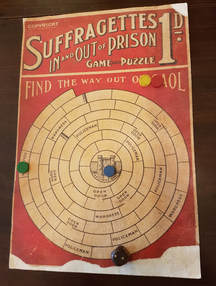

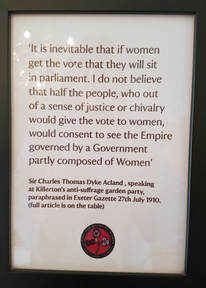

Choosing Your Ancestors

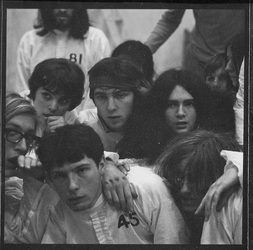

Isle of Wight Festival 1969

August 2012

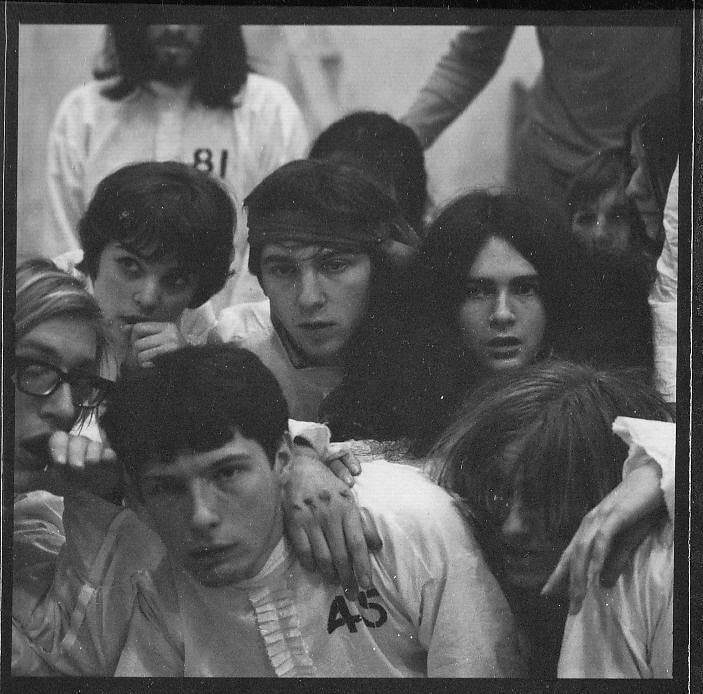

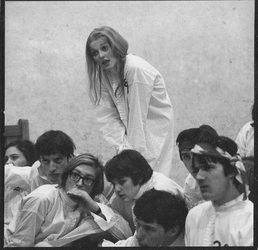

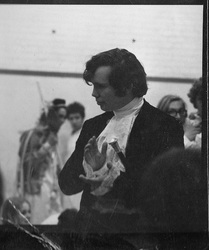

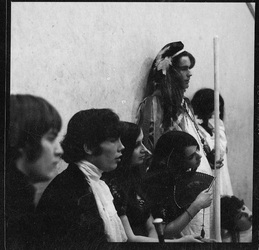

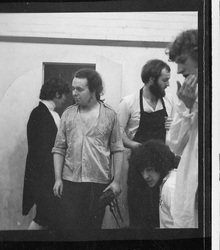

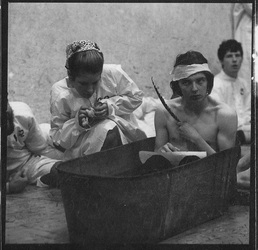

Cambridge goes mad for Marat Sade

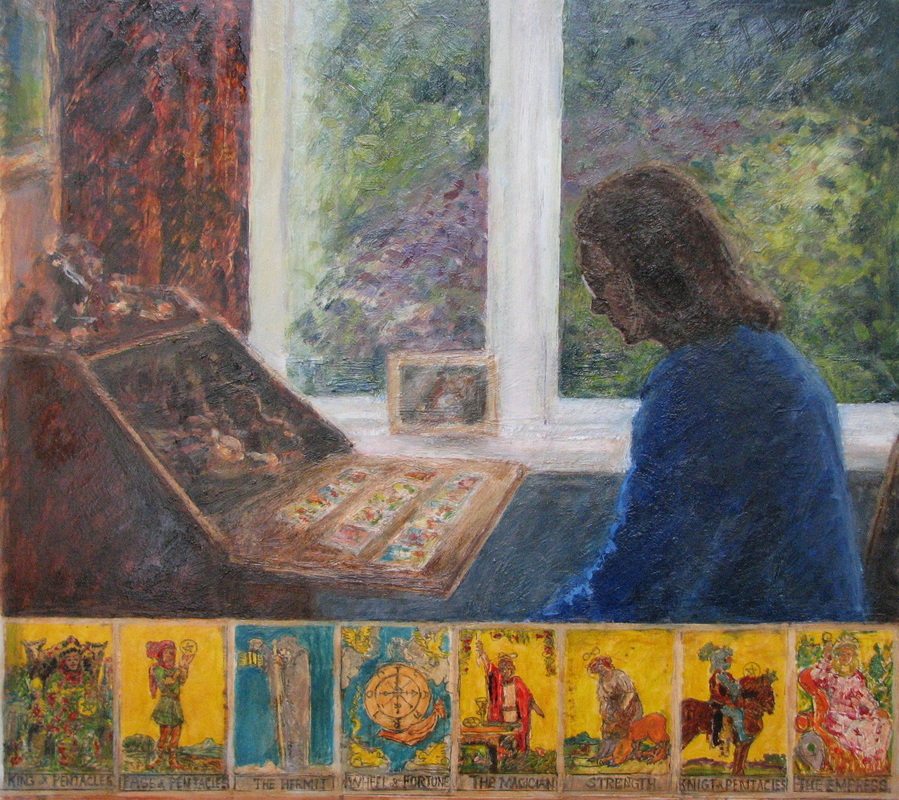

The Serendipities of Family History

September 2012

Riding the White Horses of the Camargue

Haiku for White Horses

October 2012

When is a Short Story like a Russian Box?

January 2013

Marat Sade Revisited, with a Touch of Downton Abbey

April 2013

Everyone has a Laurie Lee Story

October 2015

New Poem for a New Day

March 2016

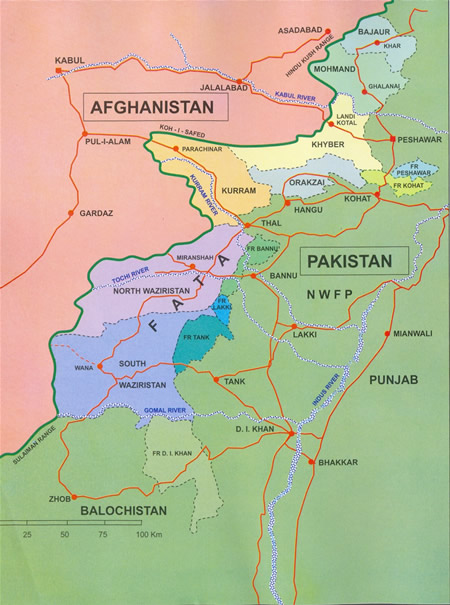

The Waistcoat from Waziristan

August 2018

Struan – Sublime Harvest Bread

RSS Feed

RSS Feed