When is a Short Story like a Russian Box

When is a Short Story like a Russian Box?

Taking writing tips from an unusual source

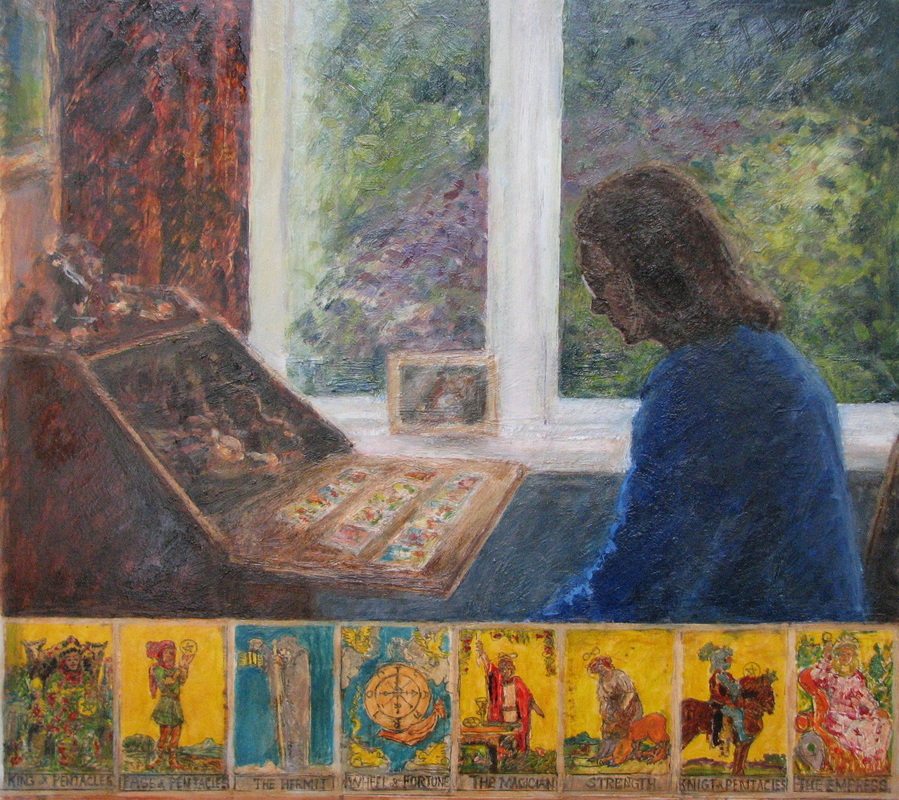

For twelve years I travelled frequently to Russia, visiting artists and craftspeople there. Why would a writer take up such a way of life? Well, this writer has trading genes too, plus an enduring fascination with traditional cultures and stories, which have provided material for several of my books. I found the combination of Russian legends and vibrant folk art irresistible, and I began a business with the aim of bringing Russian traditional arts and crafts to this country. While I made these trips, from 1992-2004, I spent as much time as possible in the four villages where the famous Russian lacquer miniatures are painted. There I talked to the artists and observed how they train and work. I should mention that this also involved celebrating with them frequently - at New Year, birthdays, picnics and just about any other occasion that was good for a shot of vodka and a few toasts!

To give a little background, these miniatures are beautifully executed paintings in tempera or oils, on a papier mache base which is usually in the form of a box. They are lacquered to finish which gives a depth of colour and a luminous quality. Mostly, they portray Russian fairy tales, and they have their roots in the art of icon painting. This gives them a timeless quality. But the art form needs a strong technique. Miniature painting is exceptionally demanding, and there is no room for anything surplus or irrelevant.

I’d like to pass on to you four specific ideas that I gleaned from these artists, and to suggest how they might be applied to writing short stories.

Shape your story carefully

The Russian miniaturist prepares a new composition with great care, usually by making at least one detailed sketch. He or she must be satisfied that it will work as a whole, and ensures that all elements are integrated, so that there is overall harmony.

In terms of the short story, it’s important to get the structure sorted before beginning the actual writing. Does it hold together as something with a beginning, middle and end, which can be written in a relatively short span? Does it have a narrative arc, and does every occurrence play a role in the story? There is no spare room for asides or diversions.

I recently interviewed author Roshi Fernando, who has written Homesick, a prize-winning collection of linked short stories. She exhorts writers to: ‘Plan, plan, plan! Understand where the story’s going. Even if you don’t know all the details, or it’s still hovering in your subconscious you need to have an idea of what’s going to happen.’

Roshi herself works by mapping out the stories on a large sheet of paper, connecting up ideas in a diagrammatic way, listing points to research, key themes and symbols, and incidents to include. This is her equivalent of the artist’s detailed sketch.

‘Every face must express an idea’

Sometimes there are many figures in Russian miniatures – perhaps twenty or more in a painting that measures only around 13cms across. The very best miniaturists make sure that every single one has a place in the composition, it, and expresses individuality. ‘Every face,’ as one highly-esteemed master told me, ‘must express an idea.’

In short stories, there’s a similar need to assess how many characters to include, and make sure that there is a genuine place for them in the narrative, even if they only appear briefly. They should not be over-characterised, but there has to be ‘an idea’ for each one which serves the story.

Create a combination of poise and dynamism

Unlike short stories, lacquer miniature paintings can’t usually tell the whole story (usually a fairy tale or historical myth) within the one image, so they have to pick one episode to portray. A crisis point is often chosen, but it has to have both poise and dynamism within that depiction. It must be active, but not hectic; we must see clearly what’s going on, but also have an intimation of what has come before, and what might follow. Here, perhaps, artistic technique doesn’t translate directly into writing, but we can draw from this the idea that anticipation and excitement must be built up, but that each moment should have its sense of grace and poise, a kind of clarity that is never overwhelmed by pace or action. We can savour each scene in its own right, while still being propelled forward in the narrative.

Acknowledging and using resources

Finally – although this might come prior to any painting or writing – comes the notion of placing oneself within a noble lineage. Lacquer artists study work that has already been created, and consider it a privilege to paint as inheritors of a tradition. The tradition includes the folk heritage which artists dip into for inspiration: fairy tales have deep significance, communicating ‘the wise thoughts of poor people’, I was told.

So, as writers, we need to investigate our own heritage. In other words, as Roshi Fernando tells us: ‘The only way that you can become a writer is to read - that’s the basis. Read every type of short story, and then experiment.’ Our literary sources may come from a wider range of eras and styles, but the principle is the same. And lacquer artists do experiment; they stretch the boundaries by trying out new colour palettes, contemporary themes – even space travel, for instance – and generally exploring their individual talents and interests. It doesn’t always work, and fit the genre, but that’s part of the creative process. We can take risks too, as writers, and sometimes, something marvellous may come from that.

This article was originally commissioned for the website of the National Short Story Week Copyright Cherry Gilchrist 2011

RSS Feed

RSS Feed