| I am fascinated by the paradoxes and contradictions in the Tarot cards. For instance, the Hanged Man (Le Pendu) is generally shown as a man suspended upside down from a cross pole by his foot. Standard Tarot interpretations often talk about hanging as a punishment, suggesting the figure is a traitor, criminal, or has been unjustly sacrificed. But, wait – he is far from dead, looks perfectly happy, and is only strung up by the foot, not the neck. Turn him up the other way and he’s fine! So what is he doing in this position? Symbolically, we can talk about shamanic practices and mythical reversals: the god Odin hung himself upside down on the World Tree for nine days in order to penetrate the mysteries (he emerged with knowledge of the sacred Runes). But in the context of Tarot history and its home in warmer, mostly Mediterranean countries, the chilly Viking god can only be a cross-reference. No, how about an acrobat? In some very old versions of the Tarot, the Hanged Man is holding a bag in each hand which look like weights. And there are accounts of pole acrobats and rope dancers who did tricks very like this. An eye witness account in modern times reports seeing an itinerant acrobat in France in just the same position as the Hanged Man of the Tarot. What about this custom from Girona, in Northern Spain? At the time of the Black Death, it had to be sealed off from the rest of the world. During the weeks or months that they were cut off from all their fellow citizens some of the residents decided to cheer up their neighbours with displays of acrobatics from poles erected between the narrow buildings. http://gironablog.blogspot.co.uk/2008/05/some-girona-legends-tarl.html. Now this is commemorated every year in the Festival of the Tarlà, with a lifesize figure suspended from a pole. Admittedly, he’s not upside down, but still gives the sense that somersaulting and hanging suspended are part of the spectacle. So I think we have here in the Tarot not a tragedy or an unhappy end, but a figure who is willingly turning himself the wrong way up, showing off his skills, defying gravity, but at the same time representing a new way of seeing the world. The Tarot’s images are resonant with symbolism, but they are also rooted in culture and history. Sometimes the actual historical context seems less important when it comes to interpreting the cards, but here I’d say that digging out the origins of the image can contribute enormously to our understanding. Work in progress! Pictures from top: the so-called 'Charles VI Tarot, prob. 15th c Italian 'Tarla' doll, Girona Jean Noblet Tarot, French c. 1650 Others from French & Italian packs in my possession |

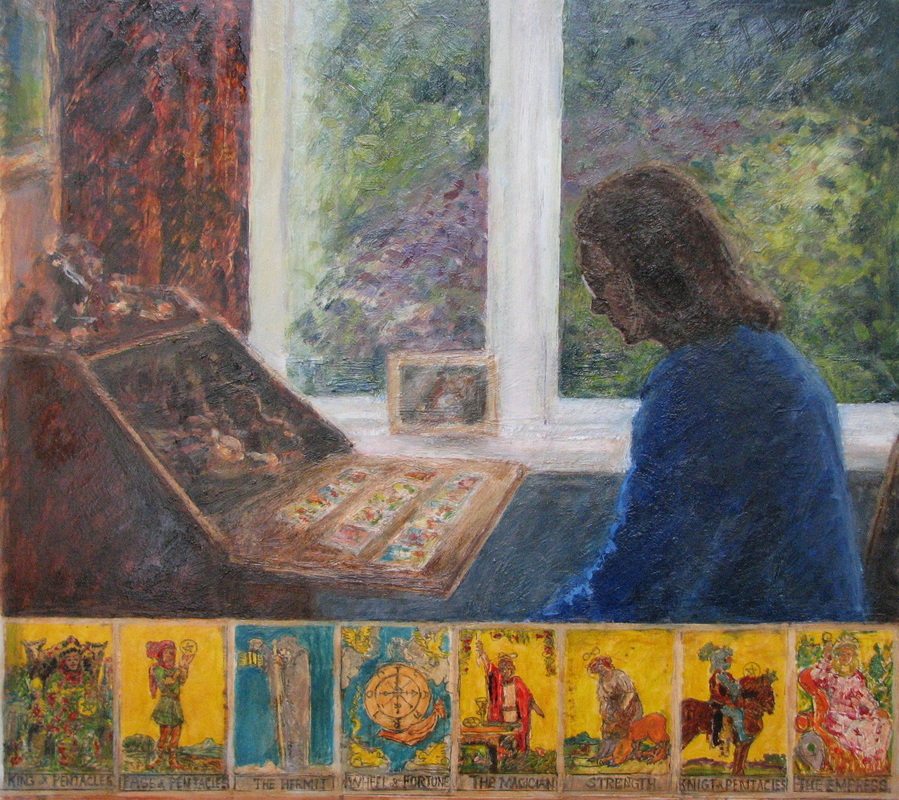

| Now I am working on Tarot Triumphs, a book to be published by Quest, USA. Our house is a hive of Tarot activity. In my office on the first floor, I’m studying the cards, writing up notes and investigating historical info on line. Up above me, in his studio, my husband Robert is drawing images of the cards, which will be used to illustrate the book. I have studied the Tarot since my late teens, but I’m doing a conscious re-visiting of every single card now. I take a card a day – in theory! in practice it often takes two or three days – and absorb its imagery all over again. I look up references, and compare packs. Only the trump cards of the traditional pack (commonly known as the ‘Marseilles’) will be used, but I’m fascinated by the history of the Tarot and love to look at ancient examples, especially the high art cards of Renaissance Italy. Colour and images swim into my dreams – I am dreaming vividly, symbolically, in a way that I haven’t done for some time. And I see anew how the significance of each Tarot card weaves its way through my life. Today – ‘Strength’ – a woman opening a lion’s jaws deftly, gently. Yes, I can learn from her. How to temper energy, and wait patiently until the moment is right. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed